(the article has been updated since its original inception, with the inclusion of Mr.Frewins' remarks about Kubrick's guidelines in choosing a title)

Yes, the title is wrong. And yes, there is a spelling mistake. What is even more surprising is that the title of this post was also a tentative title for

2001: A Space Odyssey, and it was only one of the many Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke considered for their sci-fi project.

Let's start (how could I miss it in the original post of the article!?) with

Anthony Frewin, Kubrick's aide since

2001, and his recollections about the director's habits in choosing titles for his movies. It comes from a larger and incredibly interesting article about "SK's titles waiting for a script" included in the essential Taschen's book

The Stanley Kubrick Archives.

To ask if a film's title was important to SK is like inquiring if the doctrines of the church are important to the Pope. The title was vitally important, and sometimes it seemed that SK was devoting as much time and energy in getting the title right as he was on finishing the script itself.

He figured that the first thing anyone saw or heard of a film was its title and, reasoning that there was non second chance to make a first impression, it had to grab them by the lapels there and then.

"Think of it this way. You pick up a listings magazine and there's a page, maybe two, maybe more, of fim titles - three columns on every page in eye-busting 5pt type. You've got to grab the audience then!"

So, what were the ingredients of a good title? SK argued that it had to suggest something of the film and yet not give too much away. It had to be intriguing, memorable, and short. And it had to have those x-factor poetics that made it different, but not too different that it went off the Richter Schale (and into the art house circuit).

Like all rules, these were made to be broken, but SK thought that these were the guidelines that should be adhered to whenever possible.

1. The New Frontier

The most well-known temporary title that Kubrick and Clarke adopted to refer to their sci-fi project (appearing since Jerome Agel's 1972 book

The Making of Kubrick's 2001)

was

How the Solar System Was Won, a joke based upon the 1962 MGM super-production

How the west was won (remember, the director and the writer first met in April, 1964). The forty-somethings among the readers of this blog may remember the namesake TV series of the late seventies: it was actually loosely based on this movie.

Kubrick and Clarke probably meant to honour the Frontier theme and the challenge that the newly-born United States of the 19th Century met in its "expansion" to the West; in its "conquest of the Solar System" mankind was now to face another challenge, in chasing the "New Frontier" that

President John F. Kennedy evoked in his famous

Rice University speech in the same year 1962:

What was once the furthest outpost on the old frontier of the West will be the furthest outpost on the new frontier of science and space [...]

President Kennedy at Rice University. (Source) The now iconic speech (

"We choose to go to the moon...") became even more relevant a few years later, after the tragic death of the President. Some historians even go as far as to say that

Project Apollo, once considered as a "

moondoggle", became - after Dallas - a shrine to the President who inspired it, and was thus able to survive political opposition and the progressive detachment of public opinion following the accident of January 1967, in which three astronauts died as a consequence of a

fire during a launch pad test.

So, when Kubrick & Clarke, in 1964, set out to write a movie that wanted to depict with sense of awe and wonder - while being as scientifically accurate as possible - the exploration of space, they naturally choose to use the Western "paradigm", as it was culturally dominant at the time. It is to be said that the title was not ever considered as definitive: in

The Making of Kubrick's 2001 the director recalls (p.138)

"'How the Solar System was won' was never a title that was considered".

and Clarke:

"[It] was our private title. It was exactly what we tried to show.""

How the West Was Won, 1962 (Source) But there were other, more matter-of-fact reasons for the authors' fascination with the West. As you can tell by the unusual curve of the movie screen in the picture above,

How the West Was Won was shot in

Cinerama, a widescreen process that, originally, simultaneously projected images from three synchronized 35 mm. projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen.

Cinerama was the first of a number of novel processes introduced during the 1950s, when the movie industry was reacting to competition from television. Cinerama movies were presented to the public as theatrical events, with reserved seating and printed programs, and audience members often dressed in best attire for the evening. This was the same plan MGM and Kubrick wanted to follow for the release and distribution of

2001, because it was conceived as part of a production/distribution deal between MGM and Cinerama Releasing corporation.

Most important was the fact that

How the West Was Won was a massive commercial success: produced on a then large budget of $15 million, it grossed $46,500,000 at the North American box office, making it the

second highest grossing film of 1963. (Remember that

2001 started production with a $6 million budget.)

The plan was changed after many production problems arose (among which

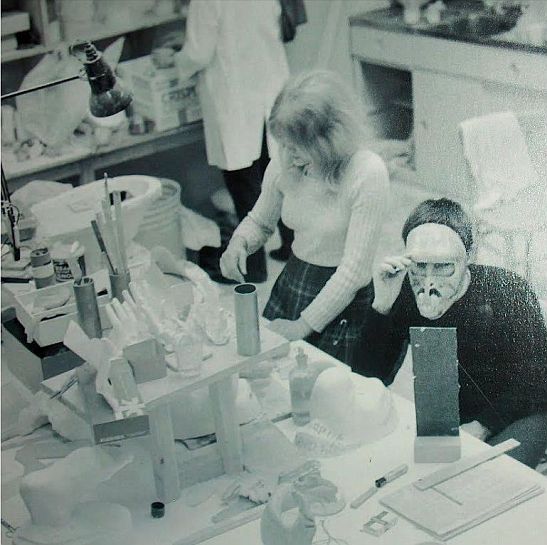

distortion problems with the 3-strip system), and following the advice of special photographic effects supervisor

Douglas Trumbull and film editor

Bob Gaffney,

2001 was shot in

Super Panavision 70, a format which uses a single-strip 65 mm negative.

It is important to remember that, quoting from the excellent website

in70mm.com,

with rare exception, post-1963 Cinerama was Cinerama in name-only. Post-’63 Cinerama is recognized to be single-strip 70mm, not the original 35mm/six-perf three-strip format.

So the same economical and technical considerations made for

2001 basically limited the future success of the three-camera Cinerama experiment to a very small amount of productions.

2. A 'Universe' of coincidences

In strict chronological order, however, the very first working title that the duo adopted for their science fiction effort was

Project: Space; that is the title that appears in a "movie outline" manuscript conserved at the

Kubrick Archive in London and that carries the date

July, 1964. The document, not long enough to be considered a treatment, let alone a script, was conceived, as Clarke explained in a

1986 interview[as] a way of getting in a whole novel in about six pages, having all of the fun but none of the work.

Clarke used to refer ironically to the movie also as

"the son of Dr.Strangelove": Kubrick's dark comedy debuted in January 1964, only three months before the first meeting between the director and the writer, and casted a shadow over the whole project that followed it, in a more significant way than usually considered (see for example

Peter Kramer's excellent book

2001: a space odyssey, BFI Film Classics, where we find out that a prologue featuring aliens was to be included in

Dr.Strangelove).

In that summer of 1964, the "movie outline" document evolved to the size of a short story now called

Across the sea of stars. The "sea" metaphor was again used by Kennedy in the aforementioned 1962 speech, when he called space "this new ocean":

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war. (source)

This "sea" concept will came back in a later stage of the development; more about that later in the next chapter.

In the remaining weeks of 1964 Kubrick and Clarke quickly went through a list of more titles: in

The Lost Worlds of 2001, Clarke recalls that the other that were considered were

Universe, Tunnel to the Stars and

Planetfall.

Universe might be an explicit homage to the 1960

documentary from the National Film Board of Canada that Kubrick saw while in pre-production.

'Universe' poster, 1960 (Unknown source)

Universe may be NFB's most honoured film; it was nominated for an Oscar and won not only the Jury Prize for Animation at the Cannes Film Festival, but more than 20 other major awards. This 26-minute masterpiece, directed by Roman Kroitor and Colin Low, featured animations of the stars and the planets to such a level of precision and realism that Kubrick contacted the directors for a job. The duo were not available because of previous arrangements, but the narrator of the documentary

Douglas Rain ended up being the voice of HAL, and

Wally Gentleman, animator and special effects expert, did optical effects for 2001.

This fact alone would be enough to make

Universe a very significant name in the Kubrick-Clarke space-time continuum: on top of all that,

Parker Brothers used the same name to launch a

Pentomino board game in late 1966 (in advance on the release date of the movie, April 1968). Its theme was based on an outtake scene in which Dave Bowman is playing a two-player pentomino game against HAL (as you may remember, the movie in its final form shows instead Frank Poole playing chess against the computer).

Universe boardgame box, 1966 (Source) Bowman playing pentominoes vs.Hal. (source) Here's a PDF file with the original instructions, courtesy of Hasbro that holds the copyright of the thing, and

another PDF with a longer analysis of the game. Parker Bros. must not have been happy with the scene being cut. A chronicle of the whole marketing and tie-in program conceived for

2001 would fill an entire book, as it was ground-breaking and innovative in its own.

The last title of the trio considered,

Planetfall, became in 1983 a

space-based videogame and, eventually in 2005, a

sci-fi movie. It is a term used mainly in science fiction, meaning a landing or arrival on a planet after a journey through space.

And that brings us to...

3. From 'Journey' to 'Odyssey': space myth-making

When the time came to submit to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer the tentative script in order to guarantee the financing for the actual movie, Kubrick and Clarke opted out for a sci-fi sounding title that kept an adventurous tinge with an explicit connection to space.

Here is the official press statement issued on

February 22, 1965 by MGM: Stanley Kubrick's new project after Dr. Strangelove was to be known as

Journey Beyond The Stars.the original press statement for Journey Beyond The Stars (Source)

There was something in the air, it seems: a 15-minute 70 mm. space documentary called

Journey to the stars had already been shown at the

Seattle World Fair in 1962.

Still in April 1965, in a

New Yorker interview, Kubrick and Clarke referred to the project as "Journey". In that word already lied an element of the other paradigm that the duo was exploring: the

mythologicalelement of a story set in space. As Kubrick himself said in that interview,

About the best we’ve been able to come up with is a space Odyssey–comparable in some ways to Homer’s Odyssey,’ said Mr. K. ‘It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation, and that the far-flung islands Homer’s wonderful characters visited were no less remote to them that the planets our spacemen will soon be landing on are to us. Journey also shares with the Odyssey a concern for wandering, and adventure.

Two entries in Clarke's diary for 1964, right at the beginning of the production, were already pointing us to the growing "myth-making" intentions of the director:

July 28. Stanley: "What we want is a smashing theme of mythic grandeur."

September 26. Stanley gave me Joseph Campbell's analysis of the myth "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" to study. Very stimulating.

In fact, in his 1973 essay

The Myth of 2001 Clarke states clearly that

It is true that we set out with the deliberate intention of creating a myth. (The Odyssean parallel was clear in our minds from the very beginning, long before the title of the film was chosen.) A myth has many elements, including the religious ones.

The so-called "Hero's Journey" (or

Monomyth) is one of the oldest archetypes of literature and storytelling; a story structure that seems to have occurred in many of the major myths and religions throughout human history - Homer's

Odyssey as the most famous - as first theorized, in the late 1940s, by the famous mythology professor

Joseph Campbell. As an analysis of its importance in the making of

2001 would go beyond the scope of the present post, I would like to state that

2001 is

oftenused by

scholars as an

example (along with

Star Wars), albeit

bizarrely structured, of the

use of this classic story.

Neither the director nor the writer, anyway, were satisfied with

Journey Beyond The Stars, as the latter recalled in

The Lost Worlds of 2001:I never liked this, because there had been far too many science-fictional journeys and voyages. (Indeed, the innerspace epic Fantastic Voyage, featuring Raquel Welch and a supporting cast of ten thousand blood corpuscles, was also going into production about this time).

We're catching up, at last, with the title of this post. In a cover of a script still titled

Journey Beyond The Stars (therefore presumably dated 1965) that appeared in the book

The Stanley Kubrick Archives, Kubrick himself (his handwriting is easily recognizable) jotted down some more tentative titles:

Earth Escape,

Jupiter Window, the evocative

Farewell to Earth (obviously reminiscent of Hemingways'

Farewell to Arms, is also the title of one of the many tentative scripts abandoned by Clarke and reprinted in

The lost worlds of 2001); in the center of the page, a title with a subheading:

The Star Gate / A Space Odessy (

sic). It appears as if Kubrick was trying to convey, by trial and error, the epical subtext of the adventure that his Odysseus, Dave Bowman, was about to undertake: at the end, citing explicitly The Odyssey, he went back to the original source of inspiration. In these titles we find as well a significant departure from the concept of "conquest" as in the West: Man must abandon ('escape') Earth not for the sake of conquest or possession, but rather in order to gain a sense of one's existence, both personally and as a species.

I like to consider the inclusion of the 'Star Gate' as a reference to the monolith, the

Jungian archetype Kubrick referred to it in a

1970 interview - Campbell himself was inspired by Jung and his concept of 'collective unconcious' - that in the movie appears with the function of symbolic 'threshold' that the Hero must cross in order to accomplish his journey and return home.

At last, the director concludes his personal naming odyssey with the definitive title that we all know today (in the uppermost left corner of the picture above), using the symbolic date of the first year of the new century, followed by the correct spelling of the subheading. The use of the conjunction "a" is, to me, a kind nod to the 'other' Odyssey: Kubrick's journey belonged to space as Homer's to the sea.

We leave the conclusion to Arhur C. Clarke, again from

The Lost Worlds of 2001:

It was not until eleven months after we started -- April 1965 -- that Stanley selected 2001: A Space Odyssey. As far as I can recall, it was entirely his idea.

Book sources:

- Agel, J. (Ed.), The Making of Kubrick's 2001, The New American Library, 1970

- Castle, Alison (Ed.); The Stanley Kubrick Archives, Taschen, 2006

- Chapman. J., Cull, N. (Ed.), Projecting tomorrow: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema, Tauris, 2013

- Clarke, A.C.; The Lost Worlds of 2001, The New American Library, 1972

- Kramer, P.; 2001: A space Odyssey, BFI Film classics, 2010